Prof. Dr. Anna Hirsch

Duration

Funding Saarland

Total funding

Number of partners

Worldwide, it is becoming increasingly difficult to fight many bacterial infections because of the bacteria’s resistance to antibiotics. Infectious diseases are thus more difficult to treat, which can lead to serious complications in some cases. Against this background, drug research aims to develop drugs with a novel mode of action. Thanks to new analytical methods such as the sequencing of entire genomes, scientists have detailed biological information at their disposal. The starting point for the development of a new active substance is the identification of a target protein - a so-called "drug target" - which has a key function in a disease. This is also where the research work of Anna Hirsch begins. She is using innovative methods in her ERC project to identify new molecules that affect these target proteins in a specific way, thereby laying the foundation for the development of a new drug.

“The potential that the results of my research might actually help people at some point in the future has always motivated and driven me.“

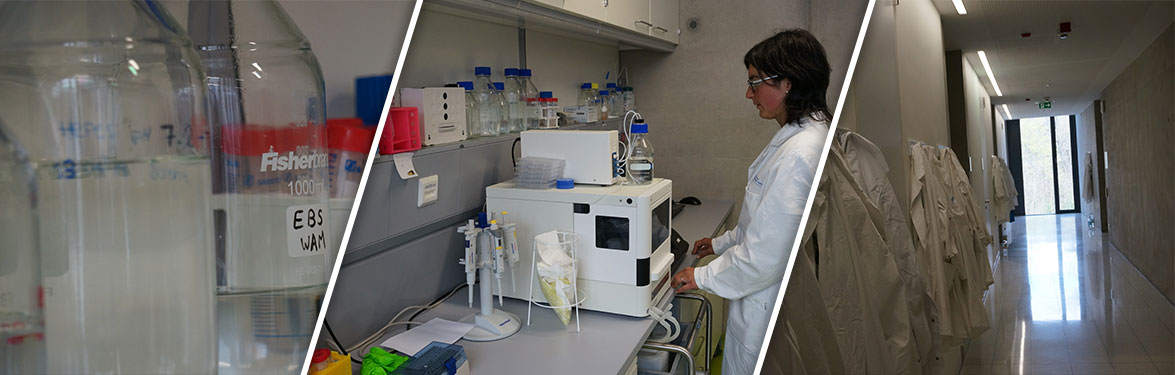

Anna Hirsch has been researching the development of new drugs against infectious diseases at the Helmholtz Institute for Pharmaceutical Research Saarland (HIPS) since 2017 - among other things with the help of a Starting Grant from the European Research Council. Next to her work at HIPS, Anna Hirsch is a Professor of Medical Chemistry at Saarland University. We met her for a talk.

Could you briefly describe your research area and interest?

My research interest is primarily in the field of so-called "anti-infectives", i.e. the development of new drugs and therapies against infectious diseases. This is also the research focus at the Helmholtz Institute for Pharmaceutical Research Saarland (HIPS), where I work. In the context of infectious diseases, there is currently a growing problem with resistance development, especially antibiotic resistance. At present, this topic is also frequently reported in the media. So in this respect, it is critical to use innovative methods to find new molecules that can ultimately be developed into a new anti-infective. The basis for this is that these molecules act on new, so-called "targets". Targets are often proteins that lead to the actual therapeutic effect in our organisms, because they can be influenced in their function or structure through the molecules. And this is exactly what we are trying to do.

What are the most recent achievements of your scientific work?

Some really important “breakthroughs” that we have recently achieved were primarily in the area of methods. Here, in fact, we were able to prove that the innovative approaches that we have developed actually work. The next step, of course, is that we - and other research groups – increasingly apply these methods. We are primarily focusing on bacterial infections and here especially on the "Gram-negative bacteria", which represent the greatest risk in antibiotic resistance. For example, these bacteria are frequently found in lung infections. Last year we succeeded in discovering extremely promising molecules for various targets, which we are currently optimizing further.

What fascinates you most about your subject area? Did you always want to do research in this area Indeed, even as a student I wanted to work in this field of research, but was not sure if this would be possible. So, for my doctoral thesis I chose a topic from a similar research area. Although the main focus was on new active ingredients for the treatment of malaria, I also gained some experience in the field of anti-infectives. What I have always found particularly fascinating about this field is that, although we initially carry out basic research on the academic side, there is still a chance to develop something that could at some point actually help people. This potential has always inspired and driven me.

Since coming to HIPS, the whole thing has become much more concrete. On one hand you are expected to do high-quality basic research, but on the other you are also encouraged to pursue exciting discoveries in the direction of translation, i.e. towards concrete application. This is clearly what being part of a Helmholtz institute or center is about.

What are you currently researching? And what does the research process look like?

Essentially, we are currently working on two strands of projects: one is the research of the new methods that were previously mentioned, which we are currently establishing and for which we are looking for new areas of application. The second strand is a series of classical "medicinal-chemical" projects. Here we are looking at different anti-infective targets, i.e. different proteins, and trying to get at certain molecules by using new or existing methods that interact with these proteins and hopefully show the desired effect. These processes then usually have to be continuously improved in long-term procedures. It is important that the desired effect does not only occur in the test tube with the isolated protein, but also in cells. In the case of antibiotics, these are specific bacterial cultures in which we look at whether or not they affect bacterial growth. For the most part we can also do this here at the institute. At the same time, we check "in vitro" and then also "in vivo" whether the molecules have suitable properties for further development into an active substance. After that, the most promising molecules would be tested in initial "in vivo" infection models, for example on zebrafish or mice. This is where we want to get to with our research. If all these steps prove successful, we can start thinking in terms of clinical trials.

How long does the overall process of such a new drug development take?

In a pharmaceutical company, one generally speaks of ten to twelve years. Of course, at our Institute there is a much smaller group of people working on such projects. Accordingly, it takes considerably longer. The primary goal of our projects is to reach the so-called "pre-clinical" phase. This means that we must first show that we can achieve the desired therapeutic effect in an in vivo experiment. If the experiment is successful, a pharmaceutical company or a non-governmental organization might subsequently join the project and actively monitor or even take over the process.

How would you assess the cooperation with partners from the industry? Do you work together with pharmaceutical companies in the projects?

It is quite common for us to work with pharmaceutical companies as mentors in projects, who take on an advisory role and closely follow how the project develops. But they all basically say that they can only really get involved in the research process once an "in vivo" model has been successful. And in order to get there, one must, as already mentioned, have already done a number of sometimes very expensive studies, for which the "normal" funding sources are often not suitable or not even intended.

Another big problem is that there are hardly any companies left that carry out anti-infective research because the general business model of the majority of pharmaceutical companies does not really fit into this field of research. They usually focus on other "big" social diseases such as cancer and not on research into new antibiotics, which are only taken for a very limited period of time. This is different for asthma or high blood pressure, for example.

In addition, the development of new antibiotics is much more difficult and the risk that the process fails is much higher. And if things go well and the new antibiotic comes onto the market, one would actually want to "reserve" it mainly for the isolated cases of infections that are in fact multi-resistant bacterial strains. The vast majority of other patients would still be treated with existing preparations. As a result, there would only be very few patients who could be treated with the new antibiotics during the patent period. We therefore also need new ideas and approaches in structural terms in order to make the development of these preparations more attractive from an economic point of view. For example, there are considerations to extend the patent term for such drugs in order to be able to treat more patients within this period. But there is also a lack of knowledge and awareness of these diseases. Even though there are currently more movements and initiatives that raise awareness of the importance of research into bacterial diseases and provide new funding instruments.

Looking to the future: where would you like your research to be in 10 years?

In recent months, we have already evaluated some of "our" newly identified molecules in simple "in vivo" infection models and are continuing to work in this direction. In general, I would like to see us successfully identify one (or more) preclinical candidate(s) in the scope of our projects, which will then be taken up and further developed by a pharmaceutical company or a non-profit, more application-oriented initiative.

After several stays abroad you have been in Saarland since 2017. What brought you here and how do you rate the working conditions on site?

Interesting question: at my last station in Groningen, I actually already had a permanent position as "Associate Professor". So, I could have actually stayed there (Anna Hirsch laughs). However, the lack of third-party funding in the Netherlands was and is a shortcoming. It is quite difficult to obtain national funding and there are simply fewer grants. The latter are therefore correspondingly hard-fought. Consequently, the success rates are unfortunately also very low. In comparison, the third-party funding situation in Germany is much better and there is a high quality "basic funding", which does not exist in many other European countries. That is what really appealed to me.

But I must also admit that HIPS as a research institute really offers a fantastic, I would almost say unique, research environment:

HIPS' size is ideal, the institute has an excellent infrastructure and, last but not least, the research focus offers ideal conditions for my work. Especially the clear thematic focus brings that I can cooperate with colleagues very quickly and easily. If, for example, we don’t cover a certain area in the department, there is someone who does on the next floor. In other words, even if I don't directly need certain infrastructures in my daily work, they exist, and I can use them when I need them. The various expertise is very much bundled here, and the level of research is therefore extremely high.

What is the overall role of EU research funding opportunities for your science sector?

Basically, I have the feeling that so far it has been rather difficult to be successful in my field at EU level - whether within the framework of the ERC or with regard to larger research collaborations. Only this year, for the first time, the ERC introduced the keyword "medicinal chemistry" as an official category for the ERC. So far, it really has been rather difficult, which is also why, back then, I deliberately focused my ERC application on the methods. Apart from the ERC, the Initial Training Networks (ITN) offer interesting possibilities for cooperation. Such research collaborations in a national or international framework are undoubtedly very important for my field. In summary: I certainly have EU funding in mind, but the national opportunities are of course just as interesting. All in all, I think it is essential - independent of scientific discipline and individual institution - to consider and obtain different sources of third-party funding. That is simply part of it.

You "won" an ERC starting grant in 2017. What does this prestigious award mean to you and what does it makes possible?

In concrete terms, of course, the ERC enables me to recruit staff for the projects described in the ERC. This is a clear added value of this grant. It obviously makes a huge difference whether, for example, a BMBF-funded collaborative project provides me with one doctoral student, or whether the ERC provides me with three doctoral students, one post-doc and one technical assistant position. Furthermore, I think it's fair to say that the ERC is a kind of "seal of approval" and creates a high degree of visibility for me as a scientist - both locally here in Saarbrücken, but also nationally and internationally. I do believe that this award can have an enormous influence on future applications, prizes or vocations. It is also certainly a good starting point for possible subsequent ERC grants such as the Consolidator Grant.

Anna Hirsch studied natural sciences at the University of Cambridge (England) with a major in chemistry. She obtained her doctorate on "A Novel Approach towards Antimalarials: Design and Synthesis of Inhibitors of the Kinase IspE" under the supervision of François Diederich at the ETH Zurich (Switzerland). After a postdoctoral stay in Strasbourg (France) under the supervision of Jean-Marie Lehn, Anna Hirsch took over a position as assistant professor in 2010 and associate professor for structure-based drug development at the University of Groningen (Netherlands) in 2015. Since 2017, Hirsch has been Professor of Medical Chemistry at Saarland University and heads the department "Drug Design and Optimization" at the Helmholtz Institute for Pharmaceutical Research Saarland (HIPS). The main goal of her work is to further increase international visibility in the field of developing new anti-infectives and hit identification methods. Anna Hirsch was honored with the following prizes: Gratama Science Award (2014), SCT-Servier Prize for Medicinal Chemistry (2016) and Innovation Prize for Medicinal Chemistry of the GdCh/DPhG (2017).